The Peruvian press in the line of fire

Luisenrrique Becerra, a 29-year-old freelance photojournalist, was covering a demonstration in downtown Lima when officers from Peru’s National Police approached and him started shooting.

It was Saturday, 28 January, at around 9pm. Becerra, who works with German and Swiss outlets, had seen how the police tried to surround a group of demonstrators, shooting them with metallic pellets and tear gas cannisters. As he was photographing medics treating injured people, more police arrived on motorcycles and on foot. When he turned around, despite carrying his camera in his hand and wearing a helmet and press credentials, he saw two officers taking aim at him.

“The police were about two-and-a-half meters away when they shot me,” Becerra says. “My helmet spun violently and then I felt my face go numb… I wanted to keep taking photos until I touched myself and felt I had blood all over my hand. The pellet had struck me just between my gas mask and my helmet.”

Sharing his account with Amnesty International at a cafe in Lima two weeks later, Becerra reveals the 5cm scar that still hasn’t healed, just below his hairline. “I was glad at the time that I hadn’t lost my sight… But I was still worried about my head,” he says. “If I didn’t have this helmet, the pellet would have hit me directly in the head. It might have fractured my skull – or worse.”

The attack against him was not an isolated incident. Since the beginning of a wave of protests sparked by the announcement of the dissolution of Congress and the subsequent dismissal of then-president Pedro Castillo on 7 December, the National Association of Journalists (ANP by its initials in Spanish) has registered at least 170 aggressions against the press. These have included harassment, arbitrary detentions, shootings and death threats. During the first month, most of the aggressions were committed by protesters upset at Peru’s mainstream media for reproducing the government’s stigmatizing narratives that depicted protesters as terrorists. However, according to the ANP, police officers have been responsible for most of the attacks against the press since January.

“For us it’s clear that journalists are targets, and photojournalists especially, because they don’t want them capturing evidence of human rights violations,” says Zuliana Lainez, the president of the ANP. “The pattern we’re seeing is that every time someone photographs an arrest taking place or records evidence of excessive use of force, that’s when they’re attacked or have their equipment taken away, or they’re subjected to a narrative undermining the work of the press.”

‘I’ll blow your head off and you’ll die here’

Aldair Mejía, a photojournalist for the Spanish news agency EFE, was covering a protest near the airport in the southern city of Juliaca the morning of 7 January when police officers began firing tear gas at the demonstrators.

Mejía placed a helmet over his long dark hair and made sure his press identification was visible. As he was photographing a man helping a baby, two policemen ran up to him. Although he told them he was a journalist, they knocked him to the ground with their shields. They tried to tear up his press pass and told him: “media trash, get out of here”.

A little later, when Mejía was trying to film an arrest in an alleyway, another officer carrying a firearm told him: “Get out of here. I’ll blow your head off and you’ll die here”. Mejía put his camera away and continued on his way.

Around 3pm the confrontation between the security forces and the demonstrators intensified. Positioning himself behind the protesters, Mejía took photos of police less than a block away pointing their guns directly at them. One protester who was right in front of him was hit in the face. Mejía saw him bleeding and noticed he had “three perfect round holes in the face” where the pellets had struck him.

“Just as I was checking the photos I’d taken I was hit in the leg,” Mejía says in an interview over Zoom. “My leg went numb and in a few seconds I saw blood flowing from my right shin.” His beige shorts turned crimson. “I saw a circular hole and said: Damn, that’s a pellet… I was bleeding on the ground for almost five minutes.”

Some protesters dragged him away while the police kept shooting. They applied a tourniquet and took him to a clinic aboard a motorbike. At first, after an X-ray, the staff diagnosed him with a fractured leg due to a pellet impact. However, minutes later the clinic’s director appeared, saying a stone could have caused the wound.

Officials from the Interior and Justice Ministries arrived at the clinic, and a group of soldiers showed up outside the building. Frightened, Mejía voluntarily discharged himself so he could leave the area. At that point the clinic took the unusual step of issuing a statement claiming “an undetermined object” had caused his injury.

Mejía believes the police were deliberately trying to inhibit the demonstration and prevent him from exposing their repressive behavior.

“They were always moving in pairs and they would steady themselves before shooting from as close as possible in order to hit and wound someone and stop them from protesting,” he says. “I think they wanted to silence me or stop me from photographing anything because I was the only one from a foreign outlet there and they suddenly seemed very uncomfortable with the presence of the press.”

Two days later, police repression in Juliaca left 17 people dead. Upon returning to Lima, Mejía started to receive calls from unknown numbers. The fear drove him to abandon his home.

Differential treatment

Juliaca’s largely indigenous population has suffered a disproportionate number of deaths during the repression of protests – something Amnesty International has attributed to “a marked racist bias” on the part of the authorities. Independent journalists from the region have also reported facing discrimination while trying to carry out their work.

Julio César Jara, director of the local outlet Planeta TV, was among those who traveled to Lima to cover the protests there. Police officers beat him while he was filming the release of people detained in an operation at the San Marcos university, despite the fact that he was wearing his press vest.

“When they see you, the police yell abuse at you. They remind you that you’re indigenous with the language they use, like: we’ll kill you if you don’t leave,” he says. “It seems as if they had orders from above to use the same terms against both protesters and journalists.”

Wara Guerrero, another journalist from Juliaca who went to Lima to cover the demonstrations, says she heard police telling them: “You’re with them, you’re agitators, so we’ll have to repress you the same way,” and even “you deserve bullets because you’re terrorists.”

Female journalists have also faced gender-based discrimination when covering acts of repression. In one case, male police officers pushed and beat Graciela Tiburcio Loayza, an independent journalist and the former president of Amnesty International Peru’s board of directors, and told her she was “provoking” them.

“Whatever the form of their aggression, it always has sexist connotations,” says Tiburcio Loayza. “For example, the fact that they’re not only physically assaulting you, but taking advantage to sexually harass you too, either by whistling at you or insinuating that you liked their batons, that you liked the gas, that you want them to give you more. This all takes its toll on you, not only as a journalist, but also as a woman, because you don’t feel free or safe to do your job as a reporter.”

Likewise, Leah Sacín, a contributor to Radio Nacional and the feminist media outlet La Antígona, has noticed “a differentiated but pejorative treatment of female colleagues who cover these issues.”

Sacín says policemen have belittled her with misogynist comments like “get out of here mommy” and “why don’t you go home?” She has also suffered physical violence. During a protest in Lima, Sacín filmed police intimidating an older woman with indigenous features who was trying to leave the area and told them: “They’re peaceful people. She is a lady, treat her with respect.” The policemen responded by pushing Sacín with their shields, ripping her phone from her hands and knocking her to the ground.

Sacín believes these aggressions are “police strategies to prevent coverage, impede access and generate fear. Because obviously if they attack you, they push you, or you’re in a peaceful situation and they rain down tear gas cannisters that make you cry and hurt your throat, your desire to keep covering it is increasingly diminished.”

Peru’s National Police did not respond to requests for comment on the allegations against them.

Accusations of state censorship

Censorship is another risk faced by even the best-known journalists. Carlos Cornejo, a prominent broadcaster for the state network TV Perú, lost his job at the end of January in what he considers retaliation for his critical coverage of the security forces’ repressive behavior.

Cornejo, a familiar figure with his beard and gelled hair, says the president of TV Perú’s board of directors told him on 30 January that they were taking him off the air for a month while they carried out an evaluation of his program. Board members later told him the network would not be bringing back the show. Since Cornejo had to renew his contract at the end of each month, he says he did not even receive any compensation.

TV Perú insists his contract had simply expired and that his departure was due to “a restructuring of its primetime schedule”. Yet Cornejo suspects that the Peruvian government pressured the channel into shutting down his program.

“For two weeks on our program we’d been denouncing the death of citizens at the hands of the police,” he says. “Any attempt by Peru’s state media, which includes National Radio and TV Perú, to oppose the executive branch’s decisions, to question them, to put them under the microscope in a balanced, measured and respectful way, is seen as an attack against the government.”

His firing proved controversial. Demonstrators protested the decision outside Peru’s National Institute of Radio and Television, while the ANP criticized the network’s actions for not only violating “the journalist’s right to work, but also the collective right to information.”

Meanwhile, Cornejo says he has received ominous phone calls where the only sound is someone breathing.

‘Your life is in danger. It’s best that you don’t expose yourself’

Sometimes the threats against journalists are more explicit and come not from the authorities, but from organized crime.

Manuel Calloquispe, a freelance correspondent in the Amazonian region of Madre de Dios, has faced direct death threats as a result of his coverage of the protests.

Calloquispe, a contributor to national outlets El Comercio and Latina TV, as well as the environmental press agency Inforegión, says the attacks began in December, when he reported that criminal groups were behind the protests in Puerto Maldonado, the region’s capital city. Those groups, which dominate drug trafficking and illegal mining in the Peruvian Amazon, imposed blockades on the city, causing shortages and massive inflation in the price of fuel.

At first, Calloquispe received “insults and abuse in the street, on social networks, through WhatsApp or Messenger”. The situation deteriorated on 27 January, when a group of men surrounded his house. “Manuel, you have to get out of town,” warned a source, who shared audios and screenshots from a WhatsApp group in which they said they would attack his home.

With the help of the police, who sent a patrol car to his house, Calloquispe fled to Lima that very day. He remained there for 12 days and reported the threats to the Attorney General’s Office. But, according to Calloquispe, the authorities did not follow up on his case and he could not afford the high costs of living in the capital. He is only paid by the article, so was forced to return home in order to continue working and support his family.

However, upon returning to Puerto Maldonado, he realized the situation had grown even more volatile. On 9 February, a man linked to the group coordinating the protests in the city called him. “They know you’re here,” he said. “Your life is in danger. It’s best that you don’t expose yourself.”

Unprotected by the authorities, Calloquipse had to flee again, until the situation calmed down. Eventually he was able to return home and resume his work, but he still fears for his family: “We have no assurance from the state that it’ll guarantee our lives or our safety.”

Legal and legislative threats

Even before the protests, the Peruvian press had found itself in an increasingly hostile environment. Last year, the government proposed two laws that would criminalize journalistic work, establishing as a crime the “dissemination of classified information on criminal investigations” and increasing sentences for defamation committed through the media or on social networks.

Then, in March 2023, the Ministry of the Interior proposed a new protocol that would establish the National Police as the authority responsible for the protection of journalists. However, the protocol only contemplates the protection of accredited foreign press and members of the Peruvian Association of Journalists, potentially excluding smaller outlets and independent journalists. It also exempts authorities from any duty to protect journalists who step outside the areas recommended by the police during protests.

Far from protecting journalists, the media and various human rights organizations have warned that the protocol would further restrict press freedom in Peru. The Press and Society Institute described it as “dangerous for freedom of expression, because it proposes the regulation, under police supervision, of media coverage of protests”, while IFEX-ALC, an alliance of organizations that defend freedom of expression in Latin America and the Caribbean, stated that it contravenes international standards and the human rights treaties that Peru has signed.

Moreover, the national Ombudsman’s Office warned that the proposal “does not ensure journalists can work safe from violence, nor does it guarantee freedom of expression or information”. The protocol should protect journalists “against aggressions by members of security forces”, added the Ombudsman’s Office, among other recommendations, and should “include concrete proposals on aggressions against female journalists”.

While the authorities propose new means of control, without guaranteeing their protection, another problem the press face is that the vast majority of attacks against them go unpunished.

“There is no condemnation, not even a commitment to investigate what has happened to our colleagues, even when in 70% of the cases we might have a video that leaves not doubt that the aggressor was a member of the security forces,” says Lainez, the ANP president. “It gives carte blanche to law enforcement to think they can do whatever they like, without consequences.”

This article was originally published in Rolling Stone en español

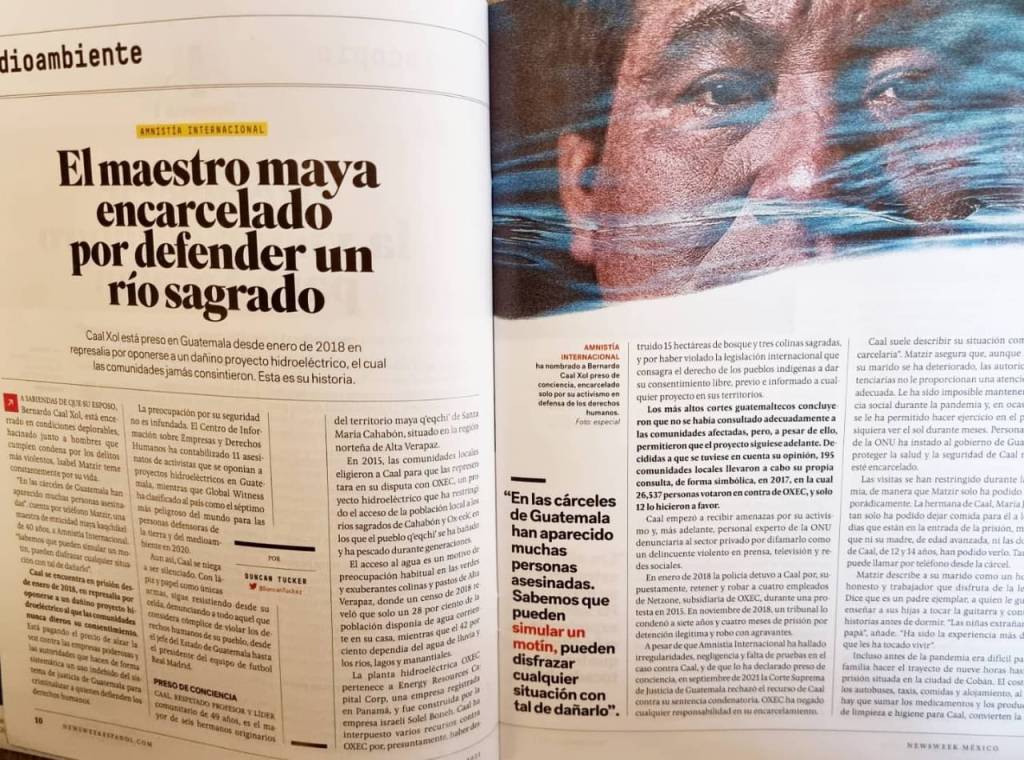

The Mayan teacher locked up for defending a sacred river

Knowing her husband Bernardo Caal Xol is locked up in filthy, overcrowded conditions alongside men convicted of the most violent of crimes, Isabel Matzir fears constantly for his life.

“Many people have been found murdered in Guatemala’s prisons,” Matzir, a 40-year-old Kaqchikel Mayan teacher, tells Amnesty International over the phone. “We know full well they can simulate a riot, they can disguise any situation in order to harm him.”

Imprisoned since January 2018 in retaliation for opposing a harmful hydroelectric project that local communities never consented to, Caal is paying the price for standing up to powerful corporations and authorities who routinely misuse Guatemala’s justice system to criminalize human rights defenders.

Concerns over his safety are not unfounded. The Business and Human Rights Resource Centre has counted 11 murders of activists who opposed hydroelectric projects in Guatemala, while Global Witness named it the world’s seventh deadliest country for land and environmental defenders in 2020.

Yet Caal refuses to be silenced. Armed only with a pen and paper, he continues to resist from his jail cell, calling out everyone he considers complicit in violating his people’s rights, from Guatemala’s head of state to the president of the football team Real Madrid.

A prisoner of conscience

A respected teacher and community leader, 49-year-old Caal is the oldest of six siblings from Santa María Cahabón, a Q’eqchi’ Mayan territory in the northern region of Alta Verapaz.

In 2015, locals nominated Caal to represent them in a dispute with OXEC, a hydroelectric project that has restricted their access to the sacred Cahabón and Ox-eek’ rivers where Q’eqchi’ people have bathed and fished for generations. Access to water is a common concern among the lush, green hills and pastures of Alta Verapaz, where a 2018 census found that only 28% of the population had running water in their homes, while 42% relied on rainwater, rivers, lakes and springs.

Caal has filed several legal challenges against OXEC – which belongs to Energy Resources Capital Corp, a company registered in Panama, and was built by the Israeli contractor Solel Boneh – for allegedly destroying 15 hectares of forest and three sacred hills, and violating an international law enshrining indigenous peoples’ rights to free, prior and informed consent over projects in their territories.

Guatemala’s highest courts found that the affected communities had not been properly consulted, but ultimately allowed the project to continue. Determined to make their voices heard, 195 local communities held their own symbolic consultation in 2017, with 26,537 people rejecting OXEC and just 12 voting in favor.

Caal began to receive threats because of his activism and UN experts would later denounce the private sector for smearing him as a violent criminal in newspapers, television and social media.

In January 2018, police arrested Caal for supposedly detaining and robbing four employees of the OXEC subcontractor Netzone during a 2015 protest. In November 2018 a court sentenced him to seven years and four months in prison for unlawful detention and aggravated robbery.

Despite Amnesty International finding irregularities, negligence, and a lack of evidence in the case against Caal and naming him a prisoner of conscience, Guatemala’s Supreme Court rejected Caal’s appeal against his conviction in September 2021. OXEC has denied responsibility for his imprisonment.

Caal often describes his situation as “torture by prison”. Matzir says his health has deteriorated but the prison authorities are not giving him adequate medical attention. Maintaining social distancing has proven impossible during the pandemic and at times he has not been allowed to exercise in the courtyard or even see the sun for months on end. UN experts have urged Guatemala’s government to protect his health and safety throughout his incarceration.

Visits have been heavily restricted during the pandemic, with Matzir only allowed in sporadically. Caal’s sister María Josefina has only been able to leave food for him with guards at the entrance, while his elderly mother and two daughters, aged 12 and 14, have not been able to see him. Nor can he make phone calls from prison.

Matzir describes her husband as an honest, hardworking man who enjoys reading. He is an exemplary father, she says, who enjoyed teaching his daughters to play guitar and telling them bedtime stories. “The girls miss their dad,” she adds. “It’s been the most difficult experience they’ve had to live through.”

Even before the pandemic, it was hard for the family to make the nine-hour journey to the prison in the city of Cobán. The costs of buses, taxis, meals and accommodation – plus the medicine, hygiene and cleaning products they would bring Caal – made it an expensive three-day roundtrip.

Under increasing financial pressure, Matzir has had to abandon the classes she was taking before he was imprisoned and adapt to life as the family’s sole breadwinner. “I had to reorganize everything financially because we have a lot of debts. The children’s tuition fees, for example, have accumulated, and we’ve postponed some surgeries that I’ve needed,” she says. “If we used to sleep eight hours, now we sleep four, five at most… this’ll have its consequences later, but for now you give every ounce of energy you have each day. There’s no other option.”

Another threat to the sacred river

Caal spends much of his time behind bars writing letters. Among others, he often denounces Florentino Pérez, the Spanish billionaire best known as Real Madrid’s club president.

Besides running the world’s biggest football club, Pérez also heads the Spanish construction giant ACS, whose subsidiary Cobra was contracted to build Renace, Guatemala’s biggest hydroelectric project, along a stretch of the Cahabón river home to some 30,000 people. In a 2014 visit to supervise construction, Pérez gifted Guatemala’s then-president Otto Pérez Molina a Real Madrid shirt and declared Renace “a project with exemplary social responsibility, with respect for others, the environment and the communities.”

Yet Caal says it has inflicted terrible harm. In one handwritten letter, he accuses Pérez of having “trampled on the rights of indigenous peoples” by piping and diverting the river without consulting the affected communities, thus “leaving thousands of Q’eqchi’ Mayan brothers and sisters without access to water”. In another, he implores Real Madrid’s fans to tell their club president to “leave the sacred Cahabón river in peace”.

The project has sparked tensions at local and international level. Shortly after a protest against Renace outside the Spanish embassy in 2017, Spain’s Chamber of Commerce urged the Guatemalan authorities to immediately disperse any gatherings, roadblocks or demonstrations that affect freedom of movement, business or private property, and “immediately initiate action, investigations and criminal prosecutions” against those responsible.

In 2019, Guatemala’s Supreme Court ordered the Ministry of Energy and Mines to conduct a free and informed consultation of the affected communities, but – as with OXEC – did not suspend the project, despite acknowledging the violation of their right to prior consent. Renace has denied any wrongdoing, but a Spanish government body found that it had caused “significant changes to some stretches of the Cahabón river… with potential negative effects on local communities.”

In April 2021, ACS announced it was selling the majority of its industrial division for almost €5 billion to the French corporation Vinci, but would hold a 49% stake in a new company joint owned by ACS and Vinci. ACS and Cobra did not respond to Amnesty International’s requests for comment.

“Florentino [Pérez] and these companies, they don’t take away the river because they really need the water to survive, do they? For them it’s just profits and accumulation,” Matzir says. “However, here in the communities it translates into the life or death of people, animals, plants, all those who live in and around the river. It’s really infuriating that there are human beings who… destroy everything in their path in order to generate profits, including people’s lives.”

Alta Verapaz is one of Guatemala’s poorest regions, accounting for 75% of nationwide child deaths from malnutrition in 2021. However, Matzir says, the authorities “never link this to access to water, to access to fish, to crabs, to snails, to all the plants that are in the river and have always served as food for the families and communities near the river. When you take away a river, you don’t just take away the water, you take away a source of food.”

Renace and OXEC say they have helped reduce malnutrition through their local health and social development programs.

Matzir also laments the tremendous spiritual blow the Q’eqchi’ people have suffered from the damage to their sacred rivers and hills, and questions why the areas where hydroelectric plants are concentrated have the least access to electricity in the country. “It’s totally contradictory. Where does this energy go? Who is it for? Where do the profits go?” she asks. “They say we’re ‘against development’ but the real question is ‘development for whom?’”

Paramilitary violence

Opposing hydroelectric projects can prove deadly in Guatemala. In January 2017, armed men fired on peaceful protesters who were demonstrating against the PDHSA hydroelectric project (constructed by Solel Boneh, the same Israeli contractor that built OXEC) in Ixquisis, northern Guatemala.

The aggressors shot Sebastián Alonso Juan, a 72-year-old land rights defender, as he tried to flee. Alonso’s family told the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights that workers from the hydroelectric plant then beat him in the face and neck while he lay in agony. He did not receive medical attention for several hours and died before reaching hospital. Local media, indigenous groups and human rights observers all implicated the plant’s private security staff in the shooting, while some also alleged police involvement. PDHSA and Solel Boneh did not respond to requests to comment on the incident.

Journalists covering the impact of Guatemala’s hydroelectric plants also risk reprisals.

Rolanda García, an indigenous K’iche’ Mayan journalist, travelled to Santa María Cahabón in August 2018 to report on illegal logging allegedly linked to OXEC. She says she was filming her final interview with affected community members when they were confronted by a group of loggers brandishing machetes.

“They asked me what I was taking photos for and demanded I delete the images,” García tells Amnesty International. The men, whom she and her companions believed to be OXEC workers, insulted her colleagues, shoved one of them and stole his tripod. “They questioned my presence in that place, which according to them was their boss’s land. And when I asked who their boss was they wouldn’t tell me, they just said it was private property.”

The men isolated García and chased her to a nearby stream, where they cornered her for about 40 minutes until she agreed to delete her photos and footage. She says they threatened to rape her and throw her in the river if she refused. Days later, OXEC denied responsibility for the attack and condemned “all acts against human dignity and press freedom”.

García says she reported the incident to the authorities but doubts her attackers will ever face justice. “In Guatemala the laws favor the landowning oligarchy and businessmen because they are the owners of the companies that operate in our territories,” she says. “Many social leaders such as Bernardo Caal Xol have been persecuted because of the construction of OXEC, and other people have been marginalized but continue to be attacked in their territories, as well as us journalists who suffer attacks for amplifying the voices of those affected.”

A former subcontractor for OXEC and Renace tells Amnesty International he witnessed the men threatening García with machetes. The man, who requested anonymity for his safety, says he worked as a welder on the hydroelectric projects but began campaigning against them after seeing the social and environmental devastation they were inflicting on the area.

He accuses OXEC of making false promises, tricking locals into selling their land and buying off others with cash and free sheets of corrugated iron to reinforce their modest homes.

“They destroyed Mother Earth and the hills that are sacred to us,” he adds, before echoing García’s complaints about the legal system. “Justice is backwards in Guatemala. Those who have money do whatever they like to those who don’t. That’s why our comrade Bernardo Caal Xol is in jail.”

A dismantled justice system

Anger at Caal’s imprisonment has coincided with discontent over systemic corruption, the dismantling of judicial independence and the erosion of Guatemala’s public institutions.

The UN-backed International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) had made unprecedented inroads in recent years, including implicating then-president Pérez Molina in a corruption scandal that fueled mass demonstrations and his eventual resignation and arrest in 2015. Yet subsequent administrations have undermined efforts to combat impunity, cancelling CICIG’s mandate in 2019 and harassing, smearing and criminalizing activists, journalists, prosecutors and judges who denounce or investigate corruption and human rights violations.

Mounting public anger at corruption, economic inequality, and the state response to the pandemic erupted in a major national strike in July 2021 after Attorney General María Consuelo Porras ousted Juan Francisco Sandoval, the head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity. Sandoval, who fled the country amid concerns over his safety, had been investigating the discovery of almost $16m USD in the home of a former infrastructure minister, and allegations of Russian businessmen delivering bags of cash to President Alejandro Giammattei. The president denies the accusations.

Indigenous leaders led the strike, with broad swathes of society joining their calls for Giammattei’s resignation and a complete transformation in how the nation is governed. Indigenous protesters blocked highways across the country, while demonstrators in the capital burned tires and threw paint over police deployed to protect government buildings.

In a letter from jail, Caal thanked Sandoval “for being an inspiration to combat the corruption that has meant death, hunger and poverty for thousands of Guatemalans” and for showing “it’s possible to achieve truth and justice”.

Sandoval is the latest of several prosecutors and judges forced to leave Guatemala in recent years, including the nation’s first female Attorney General, Claudia Paz y Paz, who fled in 2014 when authorities made unfounded accusations against her and briefly froze her bank accounts.

Speaking to Amnesty International from Costa Rica, Paz y Paz warns that the erosion of the separation of powers has further fueled political persecutions and the criminalization of human rights defenders. “There’s a pact, an arrangement between the head of the executive, the legislature and, sadly, the judiciary as well. And what worries me most is that citizens are left absolutely defenseless – not just in the face of crimes committed against them going unpunished – but also against the fabricated cases of criminalization that we’re seeing. Accusations are inflated or invented. Evidence is forged and fabricated. The situation in the country is very, very delicate.”

Paz y Paz, who made history as the first official to prosecute grave human rights abuses committed during Guatemala’s decades-long civil war – including indicting former dictator Efraín Ríos Montt for genocide – describes criminalization as “a very powerful weapon against dissidence because it implies the loss of your freedom and a very grave risk to your physical safety… It’s a way of silencing the voices that denounce corruption and impunity.”

With Guatemala failing to guarantee indigenous peoples’ rights, Paz y Paz believes international pressure and solidarity could make a difference, citing recent US sanctions on current and former Guatemalan officials for acts of corruption, and lawsuits in Canada against mining companies accused of committing violent crimes in Guatemala.

The former prosecutor also takes hope from “the excellent work done by independent journalists, as well as the few honest civil servants who remain in the country”, and the recent national strike: “civic mobilization gives us a very, very powerful voice against the authoritarianism that we’re currently experiencing in the country.”

Back in Guatemala, Matzir is equally resolute. “We have a very firm foundation in the spiritual strength of our ancestors, who have been fighting for centuries to maintain our dignity, to maintain the possibility, the hope of building a better world, a fairer world for the generations to come,” she says. “The Mayan people have faced so many situations and now it’s up to us to keep going. We have to keep the candle lit and continue defending our rights.”

Bernardo Caal Xol’s case is featured in the 2021 edition of Write for Rights, Amnesty International’s annual global letter-writing campaign and the world’s biggest human rights event. This feature was published in Spanish in the November 2021 edition of Newsweek México. A shorter opinion piece on Bernardo’s case was published in the Washington Post in English and Spanish.